A clock ticks softly—

Smoke curls, deals left unfinished,

Time burns into ash.

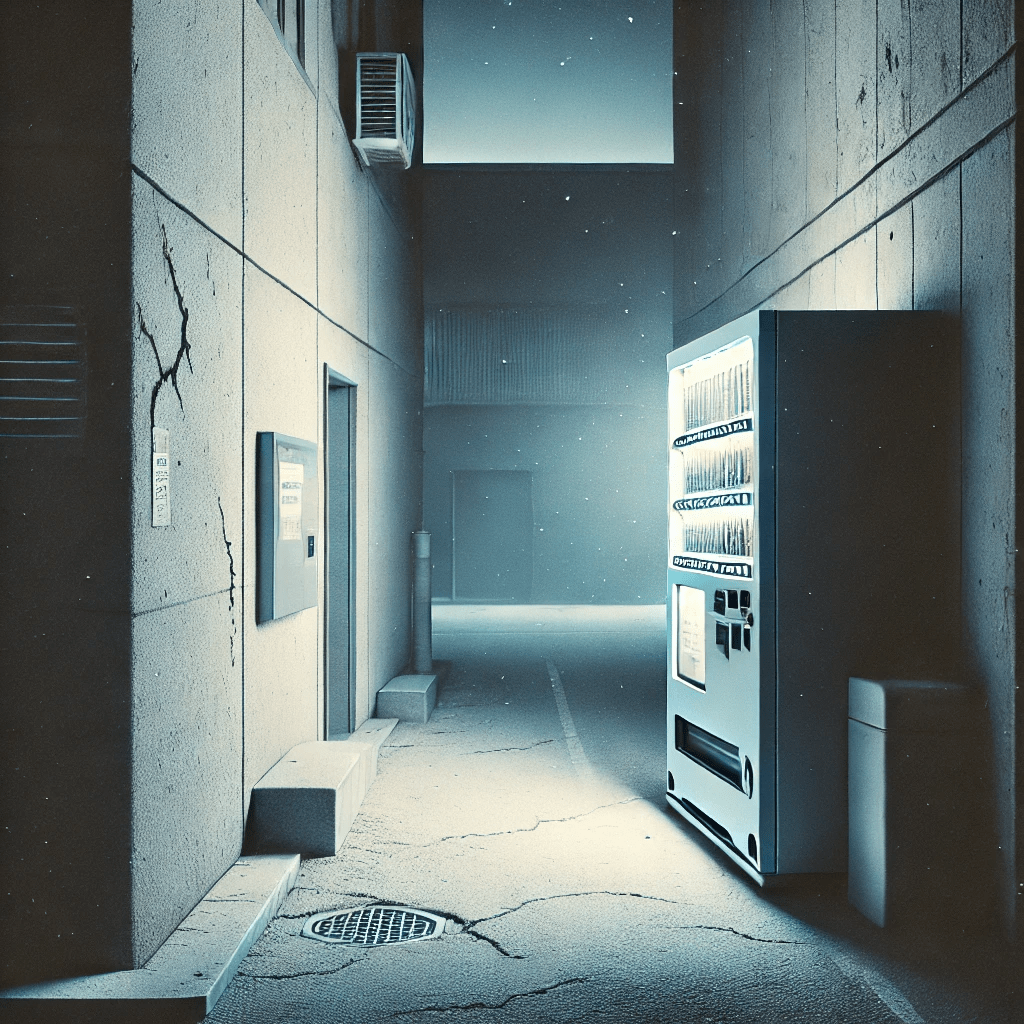

It was Tokyo, 1988—the end of the Showa era, but no one knew it yet. The economy was still climbing, but too fast, too recklessly, the yen stronger than it had any right to be. The city smelled of prosperity and exhaust fumes, of whiskey poured too easily in backroom deals, of men in crisp suits who spoke in numbers, as if they could predict the future by sheer force of calculation.

On the 14th floor of a corporate tower in Marunouchi, a boardroom hummed with quiet conversation. It was the kind of room built for power—thick mahogany table, leather chairs, heavy blinds that kept the outside world at bay. The walls, once pristine, had taken on the color of the decade—faint yellow from years of cigarette smoke curling toward the ceiling. The ashtrays were never empty.

Ten men sat at the table, their ties loosened just enough to suggest fatigue but not enough to suggest weakness. The clock on the wall read 7:42 PM.

The meeting had been going for over two hours.

Someone was talking—one of the younger executives, explaining a proposal with the conviction of a man who still believed meetings like this mattered. His voice carried across the room, measured, methodical, pressing his case like a salesman who wasn’t sure if the deal had already slipped through his fingers.

At the far end of the table, Takahashi, the oldest man in the room, had not spoken once.

His suit was darker than the others, his posture unshaken, his cigarette burning down to the filter in the ashtray beside him. He had seen too many meetings like this, too many men talking in circles, turning simple decisions into long-winded complications.

Finally, after the young executive had finished—after the words had settled into the thick air, after the others had nodded but said nothing—Takahashi exhaled, stubbed out his cigarette, and adjusted his cufflinks.

Then, he spoke.

“This meeting should have never happened.”

His voice was not loud, but it was the only thing in the room that mattered.

The younger man blinked, caught between confusion and unease.

Takahashi leaned forward slightly, his fingers pressing together just beneath his chin.

“A simple answer would have sufficed. A phone call, even. But instead, we have gathered here, poured drinks, wasted two hours discussing something that should have taken five minutes. You speak well, but words do not change reality. And reality is simple: if something is worth doing, do it. If it is not, discard it. But do not waste time pretending that words will make a difference where action is required.”

Silence.

One of the older executives coughed lightly and shifted in his seat, clearing his throat as if to reset the room. The younger man nodded stiffly, gathering his papers, his expression unreadable.

Takahashi flicked his wrist, checking his watch.

“I have a dinner reservation at 8:15. This meeting is over.”

And just like that, he stood.

The others followed a few seconds later, some slower than others, adjusting their ties, stretching their fingers, as if returning to their bodies after having been suspended in time.

Outside the boardroom, Tokyo pulsed with life—trains rumbling beneath the streets, bars filling with the quiet hum of deals that would never be signed in offices, men ordering highballs as if the economy would never break.

Takahashi walked past it all, hands in his pockets, his mind already somewhere else.

He never attended another unnecessary meeting again.

The Disease of Endless Meetings

People believe meetings are about productivity. They believe sitting in a room, discussing things at length, is the same as making progress. But meetings are where action goes to die.

- Every unnecessary meeting steals time that could be spent on real work.

- The more people in the room, the slower decisions become.

- Words do not create movement—decisions do.

- Every meeting you decline is time returned to you.

- The most valuable people do not waste their time proving their value in meetings.

The obsession with making things “perfect” through endless discussion leads nowhere. The best decisions are often unfinished, unpolished, and quick—because they allow space for movement, for refinement, for action.

A room full of men debating the best way to cross a river will drown before they ever take the first step.

A meeting that could have been a sentence is a theft of time.

A “perfect” decision made too late is worse than an imperfect one made at the right moment.

The world moves forward when people do.

Lessons in Ruthlessly Declining Meetings

- If the outcome does not change, the meeting should not exist.

- Decisions made in five minutes are often no worse than those debated for hours.

- The fastest way to get more time is to stop wasting it in meetings.

- If you are too busy for unnecessary meetings, you are doing something right.

- No one ever built something great by sitting in a room talking about it.

Takahashi reached the street just as a light drizzle began to fall, catching the neon glow of the city as if Tokyo itself was exhaling after another long day. The sidewalks were still crowded, umbrellas bobbing in and out of taxis, late-shift workers moving in slow waves toward the station.

He turned a corner, stepping past a salaryman outside a bar, still wearing his tie, still gripping a folder full of documents that would never change anything.

Inside, through the window, a group of men sat around a low wooden table, engaged in a meeting of their own—leaning in, gesturing, nodding, as if the weight of their words alone could shape the world.

Takahashi lit a cigarette, took one long drag, and walked past them without a second glance.

The city would move forward, with or without them.

Leave a comment